The death of Walter Taylor at Netley Abbey in 1704 is the most documented supernatural tale associated with the ruins. But behind the ghost story lies a real family whose influence stretched far beyond one man’s fatal accident – a dynasty of Southampton craftsmen who would go on to revolutionise British naval manufacturing.

The Legend

The story is well known to anyone familiar with Netley Abbey. In 1704, Sir Berkeley Lucy contracted a Southampton carpenter named Walter Taylor to demolish the abandoned Tudor mansion for building materials. Before beginning the work, Taylor had a prophetic dream warning him of divine punishment if he committed sacrilege against the holy building.

Taylor consulted a friend – said to have been the father of the hymn writer Isaac Watts – who urged him to heed the warning. Taylor ignored the advice and began demolition. Shortly afterwards, a stone arch collapsed and struck him on the head, fracturing his skull. The injury was initially thought survivable but, according to the earliest account, was “aggravated through unskilfulness of the surgeon.” Taylor died, work ceased, and the abbey was saved from complete destruction.

The Primary Source

Unlike many abbey legends, the Taylor story has a documented source. It first appears in Browne Willis’s History of the Mitred Parliamentary Abbies and Conventual Cathedral Churches, published in 1718-19 – just fourteen years after the event supposedly occurred. Willis describes Taylor as a “carpenter of Southampton” and provides specific details: the prophetic dream, the consultation with Watts’s father, the falling arch, the botched surgery.

The proximity of the account to the event, and the specific details about identifiable Southampton figures, suggests a genuine local tradition rather than pure invention. Isaac Watts senior was a real person – a Southampton nonconformist schoolmaster who had been imprisoned twice for his religious beliefs. He would have been in his fifties or sixties in 1704, exactly the sort of respected elder a troubled man might consult.

The Genealogical Discovery

What the legend doesn’t mention – and what appears to have gone unnoticed until now – is who Walter Taylor actually was.

Southampton records show that a carpentry workshop was established at Bugle Street in 1713, nine years after the Netley death. This workshop would become famous. It was run by the Taylor family, and would eventually be taken over by Walter Taylor III (1734-1803), described in historical accounts as “the third member of his family to bear that name and the third in a line of master carpenters.”

The third in a line. If Walter Taylor III, born 1734, was the third Walter Taylor in a carpentry dynasty, then:

- Walter Taylor III (1734-1803) – the famous block-maker

- Walter Taylor II – his father, who established/continued the Bugle Street workshop

- Walter Taylor I – the grandfather, who died at Netley in 1704

The dates align. The profession matches. The location is correct. The Walter Taylor who died demolishing Netley Abbey was almost certainly the grandfather of one of the most important industrial innovators of the 18th century.

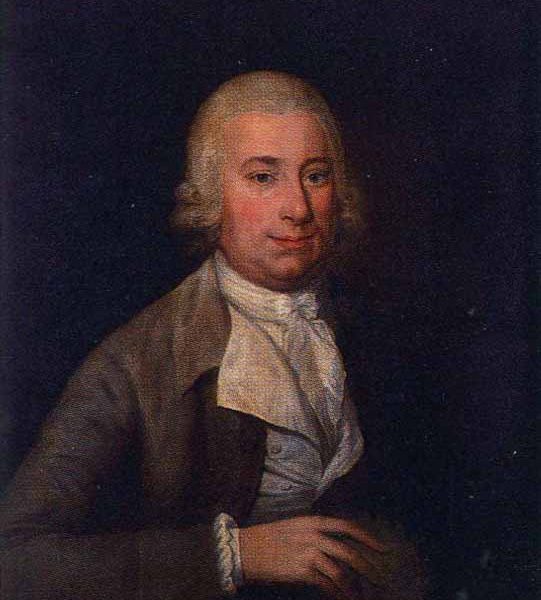

Walter Taylor III: Naval Revolutionary

Walter Taylor III transformed British naval capability. Ships of the Nelson era required enormous quantities of wooden blocks – the pulley mechanisms used throughout a vessel’s rigging. A single ship of the line might carry over a thousand blocks of various sizes. Before Taylor, each block was made by hand, a slow and expensive process.

Taylor invented machinery to mass-produce blocks, including an early form of circular saw. From his Southampton works, he supplied the Royal Navy with over 100,000 blocks per year from 1759 onwards. He held a monopoly as the Navy’s sole supplier until his death in 1803, when the contract passed to Marc Brunel’s famous Portsmouth Block Mills.

Taylor’s innovations were a crucial, if often overlooked, contribution to British naval supremacy. The blocks that ran through the rigging of every ship at Trafalgar came from the family workshop that began with a Southampton carpenter who met his end at Netley Abbey.

The Irony

There is something poetic in the connection. Walter Taylor I died in 1704 attempting to demolish a medieval building for its materials – reducing sacred architecture to commodity. His grandson would become famous for the opposite: taking raw materials and transforming them into precisely engineered components that helped build an empire.

The legend frames Taylor’s death as divine punishment for sacrilege. But perhaps it was simply an industrial accident – a carpenter taking on a dangerous demolition job and paying the price. The dream, the warning, the providential rescue of the abbey: these may be later embellishments, the kind of meaning-making that communities impose on random tragedy.

What’s certain is that the Taylor family continued. The workshop was established. The grandson revolutionised manufacturing. And Netley Abbey, spared from complete demolition by that fatal accident, survived to become one of the most celebrated ruins of the Romantic era.

Research Notes

The connection between Walter Taylor of Netley and Walter Taylor III the block-maker does not appear in any published source I have found. It is inferred from:

- Browne Willis’s 1718-19 account naming Taylor as a “carpenter of Southampton”

- Records of the Taylor family carpentry business at Bugle Street from 1713

- Contemporary descriptions of Walter Taylor III as “the third in a line of master carpenters”

- The alignment of dates, profession and location

Confirmation would require examination of Southampton parish burial records from 1704 and probate records for Walter Taylor’s estate. These should be held at Southampton City Archives or Hampshire Record Office. If any reader has access to these records, I would be very interested to hear from them.

Further Reading

- Willis, Browne (1718-19) History of the Mitred Parliamentary Abbies and Conventual Cathedral Churches

- Cooper, C.C. (1982) ‘The Production Line at Portsmouth Block Mill’, Industrial Archaeology Review, 6:1

- Coad, Jonathan (2005) The Portsmouth Block Mills: Bentham, Brunel and the Start of the Royal Navy’s Industrial Revolution