For over two centuries, visitors to Netley Abbey have been told that Richard Fox, the powerful Bishop of Winchester, was a benefactor to the monastery. The carved pelicans adorning the ruins—Fox’s personal emblem—seemed to confirm it. But thanks to groundbreaking research by historian Angela Smith, we now know the truth: the real patron was a man whose name has been forgotten by history.

The Historical Misconception

The story begins in 1798, when Catholic priest and antiquarian John Milner published his History of Winchester. While describing Netley Abbey’s “enchanting ruins”, Milner noted carved pelicans among the stonework. Since the pelican vulning (piercing its breast to feed its young with blood) was the well-known personal device of Bishop Richard Fox, Milner concluded that Fox must have been a benefactor to the abbey.

It was a reasonable assumption. Bishop Fox (1448-1528) was one of the most powerful churchmen in Tudor England, serving as Bishop of Winchester from 1501 until his death. He was famous for his munificence—founding Corpus Christi College, Oxford, building his elaborate chantry chapel in Winchester Cathedral, and supporting numerous religious houses across southern England.

For the next two hundred years, every historian who wrote about Netley Abbey repeated Milner’s claim. The pelican carvings seemed like proof enough. After all, Fox used the pelican emblem extensively—it appears carved on his chantry chapel, painted on the vault bosses of Winchester Cathedral’s choir, and even decorates buildings as far away as Durham Castle.

But there was a problem: no documentary evidence ever surfaced linking Fox to Netley Abbey. No payments, no letters, no grants. Nothing.

The Breakthrough Discovery

In the early 2000s, historian Angela Smith was researching Bishop Fox’s building activities when she stumbled across something curious in the British Library: a manuscript by William Pavey, one of the founding members of the Society of Antiquaries, who had visited Netley Abbey in 1705.

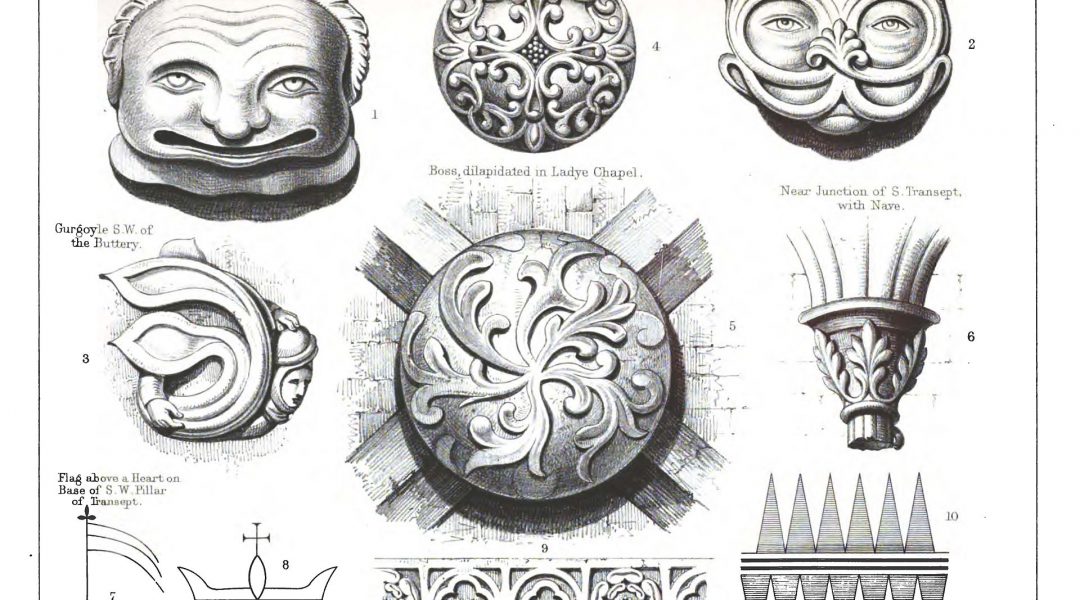

Pavey’s notes were far more detailed than later antiquarians’ accounts. He carefully recorded the heraldic shields and carved bosses that still adorned the vault over the south transept—details that would be lost to weathering and stone theft by the end of the 18th century.

Among the carvings Pavey described were shields bearing “a chevron between 3 birds (owls I think), a Rose” and another showing “the same impaling on a chevron between three roses, 3 roundels.”

These were not the arms of Bishop Fox. They were the heraldic arms of William Frost and his wife Juliana Hampton.

Who Was William Frost?

William Frost was no bishop or nobleman, but he was an influential man in his own right. Born around 1450 in Avington, Hampshire, Frost was a lawyer admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in the early 1470s. He spent most of his career serving successive Bishops of Winchester in administrative and legal capacities.

After the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, Frost was rewarded by the new king, Henry VII, with several posts including keepership of Sandwich Castle—recognition for the “loyal service he had given Henry Tudor over the seas” during his exile.

But Frost’s most significant role came in 1501 when Richard Fox became Bishop of Winchester. Fox appointed Frost as his chief steward, a position Frost held until his death in 1529. In a letter to Cardinal Wolsey in 1518, Fox described Frost as a “sadde, substanciall, feithful man, well lerned in the lawe”—high praise from one of England’s most powerful men.

Frost was more than an employee; he was Fox’s trusted right-hand man. He sat on commissions of the peace with Fox, served as Sheriff of Hampshire in 1521, and helped acquire lands to endow Fox’s new college at Oxford. The two men worked together for over a quarter of a century.

The Will That Solved the Mystery

The smoking gun came from Frost’s will, preserved in the archives of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Written in Latin in mid-1529, just months before his death, Frost’s will reveals his deep connection to Netley Abbey.

Frost requested burial at Netley “in the chapel of the Blessed Mary on the south side of that monastery, next to the place where Juliana, my late wife, is buried.” His wife had died three years earlier in June 1526 and was interred in what we now know was the Lady Chapel adjoining the south transept.

But Frost didn’t just want to be buried at Netley—he was actively funding building work there. His will describes an agreement with the abbot concerning “the new vault” being constructed “above the chapel where I have chosen my burial place.” The vault was evidently incomplete when Frost wrote his will.

To the abbot, Frost left the enormous sum of £20 (roughly £10,000 in today’s money) specifically for “painting and gilding the vault and a series of carved bosses.” These bosses—the “knotts” as Frost called them—undoubtedly included those bearing his family’s heraldic arms that William Pavey would see 176 years later.

Additionally, Frost left £40 to cover the costs of two priests who would celebrate daily mass in the Lady Chapel for seven years for the souls of himself and his late wife. This was an extraordinary bequest—the kind of perpetual chantry arrangement typically made by wealthy nobles, not professional administrators.

The Hampton Connection

Frost’s wife Juliana came from the Hampton family of Stoke Charity, who had long-standing ties to Netley Abbey. Her father, Thomas Hampton, had held several administrative posts at the monastery before his death in 1483, including revenue collector and seneschal.

It was probably through the Hamptons’ influence that William and Juliana Frost were able to choose such a favourable burial location—the Lady Chapel was one of the most prestigious spots in any medieval church, normally reserved for nobility or major benefactors.

The heraldic shields Pavey recorded tell the story: Frost’s arms (owls and a quatrefoil) impaling the Hampton arms (roses), commemorating the union of the two families and their joint patronage of the abbey.

What Frost Built

So what exactly did Frost’s money pay for? The evidence suggests he funded the complete reconstruction of the vault over the south transept—one of the final major building projects at Netley before the Dissolution.

For over a century, historians had dated this vault to the late 15th century based on architectural style. But Frost’s will proves it was built in the late 1520s—barely a decade before Henry VIII’s commissioners arrived to close the monastery.

The vault was elaborately decorated with carved and gilded bosses featuring:

- The royal arms of England

- The arms attributed to Edward the Confessor (to whom the abbey church was dedicated)

- The Frost and Hampton family arms

- Arma Christi—symbols of Christ’s Passion including the pillar of flagellation, scourges, and the pelican vulning

That pelican that misled John Milner wasn’t Fox’s personal emblem at all—it was a common Christian symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, widely used in Passion imagery throughout medieval England. Frost likely included it because Fox’s own chantry chapel at Winchester Cathedral featured similar Passion symbolism, reflecting a shared devotional interest in Christ’s suffering.

The Lady Chapel itself still stands today, though roofless. You can visit it on the east side of the south transept—a simple two-bay structure with elegant quadripartite vaulting. A medieval piscina (basin for washing communion vessels) remains visible in the south wall, marking where the altar once stood. Somewhere beneath your feet lie the remains of William and Juliana Frost, commemorated by carved bosses that have long since weathered away.

William Paulet and the Preservation of Netley

The story takes one more fascinating turn. When Henry VIII dissolved Netley Abbey in 1536, he granted the property to William Paulet, his Comptroller of the Household.

Paulet was another Hampshire landowner who had worked closely with both Bishop Fox and William Frost for decades. Like Frost, Paulet served as a steward for Fox’s various properties. The two men regularly collaborated on commissions of the peace and legal matters. In 1526, Paulet even acquired wardship of Frost’s great-nephew, Richard Waller, after Frost’s wife died. When Waller came of age, he married Paulet’s daughter Margery, cementing the bond between the families.

When Paulet converted Netley Abbey into his grand Tudor mansion, he made an unusual choice: he demolished the north transept but carefully preserved the south transept—the very section Frost had so recently renovated and gilded.

Paulet added a mezzanine floor, subdividing the lofty transept space into private apartments, but he kept Frost’s gilded vault bosses intact. He retained the Lady Chapel structure at ground level. And according to William Pavey’s 1705 notes, Paulet even added his own heraldic arms to the scheme alongside Frost’s, suggesting he wanted to be associated with his late friend’s benefaction.

Was this preservation intentional? We can’t know for certain, but the evidence suggests Paulet may have felt a personal loyalty to William Frost’s memory. In an age when most courtiers showed no compunction about thoroughly remodeling former monastic churches, Paulet’s care to preserve the south transept stands out.

As Angela Smith writes in her groundbreaking study, Paulet was “an individual caught in the middle of epic change, but one who in adapting, also sought to preserve holy ground.”

The Lost Treasures of the South Transept

Sadly, most of Frost’s carefully gilded bosses are lost. The vault over the south transept began collapsing in the mid-18th century. By 1776, only the ribs of one bay remained. By 1803, even those had been pulled down “by and for the amusement of such ignorant and unfeeling rabble,” as one outraged correspondent to Gentleman’s Magazine reported.

Some bosses were carried off by collectors. Others were acquired by the landowner Thomas Lee Dummer, who built two follies in the grounds of nearby Cranbury Park around 1770. He decorated one—a mock-Gothic tower—with approximately thirty carved bosses from Netley.

These bosses still survive at Cranbury, though badly weathered. Among them are several depicting scenes from Christ’s Passion that Frost commissioned:

- The pillar of flagellation flanked by scourges

- A pelican vulning

- Christ crucified

- The Nativity

- The Presentation in the Temple

The similarity between these carvings and the Passion imagery in Fox’s choir at Winchester Cathedral suggests Frost may have used the same pattern books or even employed some of the same craftsmen.

Other fragments from Netley found their way to Southampton’s museums in the 19th century. The Museum of Archaeology holds over thirty medieval floor tiles from the abbey, some decorated with the monogram of the Virgin Mary—likely part of the Lady Chapel pavement that Frost commissioned. Others bear the heraldry of William Paulet, marking his later renovations.

Six panels of painted glass from Netley, depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin, were recorded in the mid-19th century. They may have come from the Lady Chapel windows. Their current whereabouts are unknown—possibly lost when the Hartley Institute dispersed its collections in the early 20th century.

Why This Matters

Why does it matter that we correct a 200-year-old attribution error? Because William Frost’s story reveals something important about the final years of English monasticism.

This wasn’t a bishop or nobleman making a grand political gesture. This was a professional man—a lawyer and administrator—who chose to invest an enormous portion of his wealth in a monastery’s final beautification. He did it out of personal piety, devotion to the Virgin Mary, and love for his late wife.

Frost commissioned his vault and bosses around 1526-1529, when the writing was already on the wall for England’s monasteries. Henry VIII’s divorce proceedings had begun. Religious reform was in the air. Yet Frost poured money into gilded bosses and perpetual masses, seemingly confident that Netley would endure.

Within seven years of his death, it was all over. The monks were dispersed, the furnishings sold, the site granted to William Paulet. The gilded bosses Frost had commissioned with such care would shine for barely a decade before the Lady Chapel became part of a Tudor mansion’s private apartments.

But thanks to Paulet’s preservation and William Pavey’s careful documentation, we can still piece together William Frost’s story. When you visit Netley Abbey today and stand in the roofless south transept, you’re standing in a space that represents not just medieval monasticism, but the personal faith, family loyalty, and enduring friendship of three remarkable men: William Frost, who beautified it; William Paulet, who preserved it; and Richard Fox, whose piety inspired them both.

The Academic Research

This article is based on Angela Smith’s 2010 paper “Netley Abbey: Patronage, Preservation and Remains” published in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association (Volume 163, pages 132-151). Smith’s meticulous archival research finally solved a mystery that had puzzled historians for two centuries.

You can access the paper through academic libraries or via its DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/174767010×12747977921128

The discovery of William Pavey’s manuscript notes in the British Library (MS Stowe 845) and William Frost’s will in the Corpus Christi College archives were the key breakthroughs that revealed the truth about Netley’s final benefactor.

Visit the South Transept Today

When you visit Netley Abbey, make sure to spend time in the south transept. Though the vault is long gone, the space still conveys the grandeur William Frost intended. Look for:

- The entrance to the Lady Chapel on the east side, where the Frosts were buried

- The medieval piscina still visible in the Lady Chapel’s south wall

- The marks where Paulet’s Tudor brickwork intersects with medieval stone

- The view up through the roofless space where gilded bosses once gleamed

Stand there and remember: you’re in a place where faith, friendship, and memory intersected in the final days of medieval England. This was William Frost’s gift to his wife, to his abbey, and—though he couldn’t have known it—to us, five centuries later.

Further Reading:

- Map of Netley Abbey – Explore the south transept and Lady Chapel locations

- Visiting Netley Abbey – Plan your visit

- South Transept – Learn more about this fascinating part of the abbey